Quick background

Spectrum Brands is a rolled-up hodgepodge of assets operating four disparate divisions - Home and Personal Care (HPC), Global Pet Care (GPC), Home and Garden (H&G), Hardware and Home Improvement (HHI), something like the image below.

The thesis is rather simple - on 8 Sept 2021, SPB entered a definitive agreement to sell HHI to Assa Abloy (ASSA), for $4.3b gross and $3.5b net of tax and NOLs. HHI was first acquired in Dec 2012 for $1.4b at 8x EBITDA and so the current gross sale price at 14x fy21 EBITDA equates to 3x MOIC. The rationale of the transaction is simple - i) management believes the stock trades below the sum of its parts ii) HHI operates in a different vertical than the other more high frequency consumer product segments and the distribution avenues are dissimilar, iii) GPC and HPC are in fragmented industries with room for consolidation and so management wants more focus on them, iv) this is a great opportunity to deleverage the balance sheet and fix the firm’s cost of capital (see below).

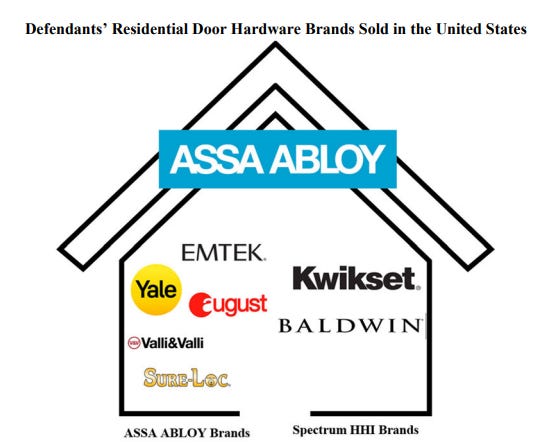

All is fine and dandy until a year later; the DOJ sues both SPB and ASSA, wanting to block the transaction on anti-trust grounds. The essential crux of the DOJ’s argument is that ASSA would obtain monopoly status and the competitive intensity currently prevalent in the market would diminish. Hence, the burden of proof is on the defendants to convince the judge that the transaction will not “substantially (note critical word) lessen competition”, in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

Case Discussion

Basically, ASSA owns overlapping brands with SPB’s HHI - Emtek competes directly with Baldwin and Yale/August competes directly with Kwikset - and the best way to alleviate horizontal merger concerns would be via a structural remedy - a divestment of overlapping assets to a competent buyer; in this case, the defendants proposed the full divestment of Emtek and the partial divestment of Yale and August i.e. only the North American business segments.

Not only that but in order to maintain competitive intensity, the buyer of said assets has to possess the wherewithal, resources and intention to compete; in other words, assuming a hypothetical private equity firm, famous for liquidating assets, comes along and offers to be the buyer, the judge may deem said P.E firm as an inappropriate buyer, rendering the structural remedy as insufficient.

In December, Fortune Brands was revealed to be the buyer of choice, offering to purchase the divested assets at 7.8x 22e EBITDA, before synergies. The market obviously liked the news and SPB shot up 20% in a day. The valuation may be a little disconcerting as the pretrial brief states that a value-purchase may disincentivise the buyer from utilizing it efficiently and this is further exacerbated by the fact that 2022 earnings are depressed (so Assa is paying 14x fy21 EBITDA on one side and divesting similar assets at 7.8x 22e EBITDA!!!). More likely than not, there weren’t many buyers that “fit the bill” and given the urgency of finding an appropriate buyer that would make the structural remedy work, Fortune obviously had the bargaining chip in their hands.

With that said, the low valuation should not be a major obstacle; for starters, I don’t see why purchasing something cheap deters one from maximizing the value therein - some of the greatest conglomerates around were formed through rolling-up of value assets. In this case, Fortune Brands is a strategic buyer with roll-up and relevant market experience via its Outdoors and Security segment brand - Masterlock; they are not neophyte entrants, they are not financial buyers, they have the distribution capabilities and based on the relevant transcripts, they clearly want to further penetrate the door hardware market. Fortune also sports 3x the market capitalization of SPB and so the pro-forma industry would have assets in the hands of companies that have more resources than SPB.

Why SPB should win the case

Despite the structural remedy proposal, the DOJ, clearly posturing (they want to litigate more merger challenges), has determined that it simply isn’t enough. So let’s go over why the DOJ may lose the case here.

Firstly, the defendants have contended that the DOJ’s market characterization is plain wrong. SPB’s Baldwin brand actually comprises of three different sub-brands and the most premium sub-brand, Baldwin Estate, of which the majority of Baldwin’s business is derived from, competes with other higher-end mechanical lock brands, not ASSA. Thus, the DOJ is overstating the proforma market share ASSA will obtain and a more accurate analysis of the competitive landscape would be simply focusing on Baldwin Reserve, which is a small % of Baldwin’s business.

Secondly, the defendants contend that Kwikset is not a direct competitor with Yale and August given that the products are distinct, with different capabilities and are sold at different price points.

Whether the contentions above are accurate is not very important as the defendants have decided to implement the divestments according to the DOJ’s assumptions; rather, they serve as an additional lever to pull when defending their case.

Moreover, we have some precedent cases to refer to. A few months back, the DOJ lost the antitrust case (presided by Judge Nichols) against the merger of United Health (UNH) and Change. Not dissimilar to our current case, UNH, to quell horizontal concerns, proposed a structural remedy to divest assets to private equity firm TPG - whilst previously mentioned that PE may not be an apt buyer, the judge determined that TPG had the experience and incentives to compete. Moreover, the court also argued that the divested assets will engender more focus at TPG (10b market cap) than under the merged UNH-Change entity (400b + market cap). Not dissimilar to our scenario, Fortune sports an 8-9b market cap and generates most of its revenues from US (84%), compared to Assa’s 28b market cap and well diversified revenue base – this should signal that the divested assets would probably thrive better with the former.

This time, Judge Jackson will preside the trial held in April; the timeline is quite tight as the merger termination falls on June 30. While Judge Jackson famously blocked the proposed merger of Anthem and Cigna in 2017, it is worth noting that for that case, the defendants were proposing a behavioral remedy rather than a structural remedy; in general, behavioral remedies are weaker.

Last but not least, the incisive language used by ASSA in their Q3 22 call is quite comforting. ASSA is paying a large control premium for the assets and analysts were questioning the rationality thereof; I wouldn’t be surprised if ASSA succumbed to buyer’s remorse and perhaps find a way to wiggle out of this; the complaint and the transcripts really point to ASSA wanting to get this deal done and given that ASSA has rolled up more than 300 businesses in 27 years, the fact that they are convinced the DOJ is irrational and completely wrong, is worth noting.

Valuation

EBITDA

SPB utilizes adjusted EBITDA which tends to deviate wildly from normal EBITDA. Figuring how much of adj EBITDA converts to free cash flow is the best way to verify the numbers. There are some accounting hulas to jump through here – if a division is up for sale, SPB could mark a business as discontinued despite receiving cash flow from it, accruing to its cash flow statement, whilst simultaneously excluding it from adj EBITDA. Hence cash flow from continuing operations is used and not the total CFFO.

A huge chunk of EBITDA is subsumed by creditors so I think the FCFF (adds back interest expense) would be a more reasonable estimate of cash conversion. 2022 is clearly an anomalous year, if we were doing up the numbers a year back, our conversion rates will be a lot tidier; ex 2022, 44.3% of adj EBITDA converts to FCFF. Pre-COVID conversion rates were a lot cleaner as well, notching >60%.

Additionally, creditors for SPB’s revolver facility are contend with using the same adj EBITDA figures (which is not always the case) and ASSA has vouched for the cash generation inherent in HHI.

Assa Abloy AB Capital Markets Day

In sum, I don’t think the conversion rates are great given that SPB is capital light - D&A runs higher than CAPEX - but we could still use these figures.

What is the market implying

Scenario 1: assume transaction falls apart and 56m of debt classified as “held for sale” is reinstated onto the balance sheet. Management guides to >$500m of cash inflow, inclusive of the 350m break fee. Using depressed 2022 EBITDA figures, we are paying 11.4x EBITDA, maybe 10x at normalized earnings, which isn’t egregious given SPB traded around this range pre-COVID.

Scenario 2: deal goes through and so at current prices, the market is imputing a 6x EBITDA multiple on the remainco. I used a 5 year average for the stub EBITDA (2018-2022) and for sanity check, management in Q4 guided to low double digit growth for fy23 - 328m would be a 15% growth over the 283m earned in 2022.

Using SPB’s guided competitor list, it is easy to triangulate a minimum of 8-12x EBITDA for each residual segment. GPC should theoretically garner the highest multiple (pet adoption tailwinds, demand inelasticity of consumables), and would make up majority of proforma EBITDA. Cascadia Capital did an analysis for animal and product retail and found that the median market multiple and transaction multiple went for north of 10x EBITDA.

Sum of the parts

A simple rough SOTP gets us to around $80 with pretty conservative consumptions (to be fair, most of the proforma value is latent in the sale of HHI) : i) valuing from depressed 2022 EBITDA, ii) penalizing the problem-child HPC with a below industry median multiple of 7x*** due to its mid-single digit margin profile and poor go-forward earnings given the pulled-forward demand during COVID i.e. everybody stocked their kitchen during the lockdown, iii) I believe GPC could garner a higher multiple like 12x which adds another $9 per share to the SOTP value (though some might argue that it’s too rich in the current market environment).

***Early last year, SPB acquired Tristar for its HPC segment for $325m cash upfront and $125m in contingency payouts. Assuming the contingency payouts are worth half of their par value, the price paid is around $390m in total. Tristar earned $546m of sales in 2021 and an assessed (i.e. theoretical) adj EBITDA of $62.9m putting the purchase price at 0.6x sales and 5.2x EBITDA. Given the steep drop off in HPC fy22 EBITDA, I don’t think a 7x multiple is overly-generous; if you value the contingency payouts at face value, then the total acquisition price for Tristar was 7x fy21 EBITDA.

Closing points

Risks

Obviously, this stock belongs to the box tagged “pretty speculative”. Assuming the deal doesn’t go through, the equity component is <50% of adjusted EV and so each turn of EBITDA is equivalent to $15 of stock price. Depending on how the market values the disparate retail businesses, the stock could get killed, especially given the impending recession we might enter; let’s not forget, the stock traded down to as low as $40 around October last year, which is the same time the S&P bottomed. On the other hand, SPB just completed possibly, the trough year; supply chains are easing, prices are being raised and inventory is being cleared progressively and so we could argue that the company is in a better position than say 6 months to a year back. In any case, with a defined timeline and tight valuation range, with some big downside, this should be sized accordingly and played through vanilla call spreads.

Value optionality

CEO David Maura owns about 1.5% of shares outstanding - $40m worth of stock on a salary base of $900k- and so value creation benefits him mutually. On that note, he has mentioned either potentially spinning off or selling HPC to a strategic buyer, to further slim down the PF entity to just pure GPC and H&G - higher margin + higher growth - which should garner a much better valuation multiple.

Disclosure: Long SPB