Variant rambles on the dicey Spirit Airlines (SAVE) merger arb

Rants on consumer surplus, HHI, odds and more

There’s quite a fair bit that has been written about the SAVE merger arb - a key one being this Substack piece, available for free public consumption. Let me preface this piece by reiterating that I am not a lawyer so all rambles are just random opinions.

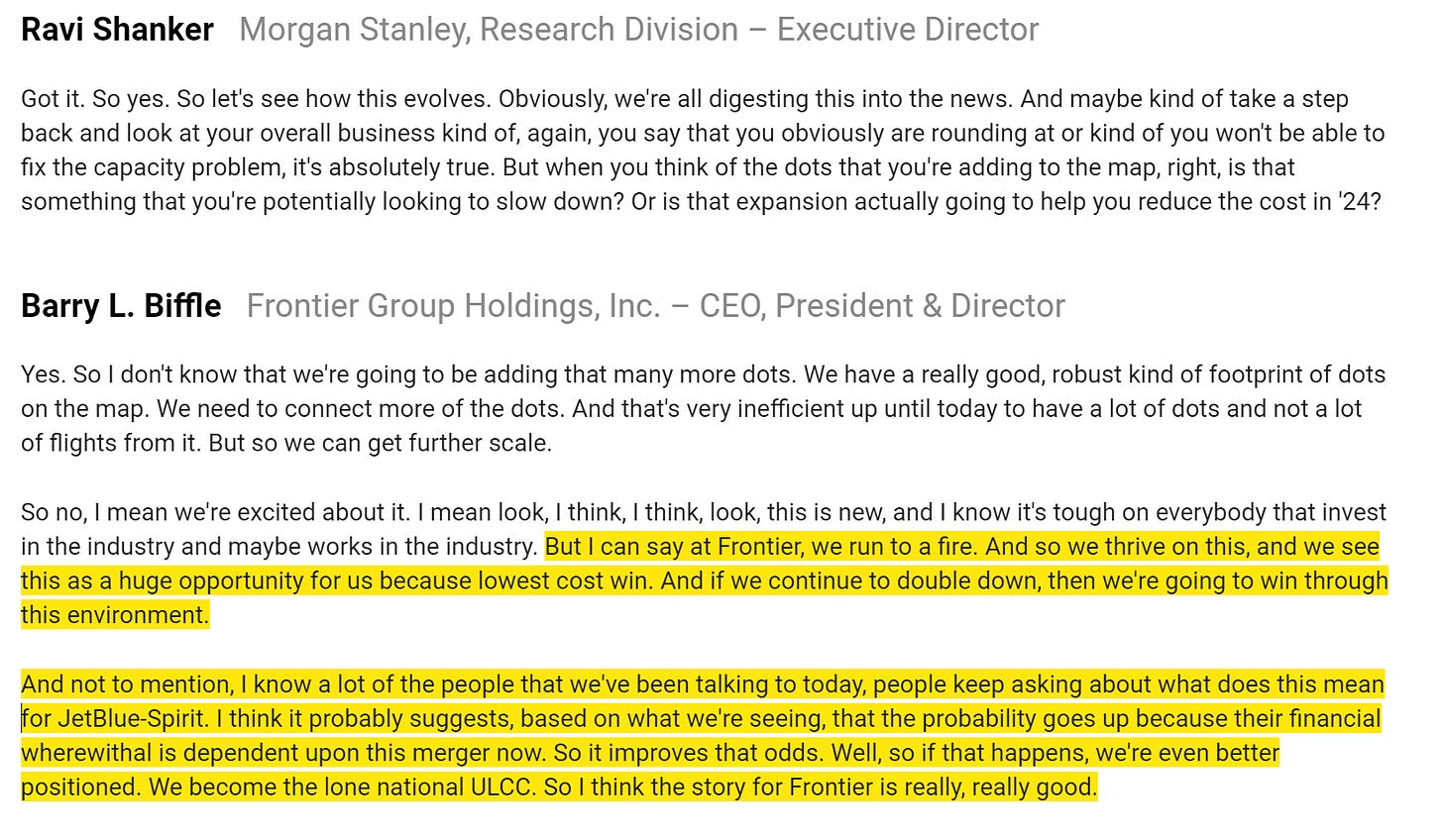

I was perusing the recent Frontier (ULCC) Morgan Stanley presentation transcript and found a few of CEO Barry Biffle’s assertions regarding the probability of closure rather fascinating.

For some background, ULCC was warning about headwinds facing the industry - demand seems to be tailing off into overcapacity and fuel costs are trending the wrong direction (up). ULCC touched upon the need to double down on cost savings as lower prices will probably be necessary to stimulate adequate demand - the evidence being the recent record travel volume surge albeit done at low price points. However, ULCC only plays a small role in the industry and even if they took capacity out, wouldn’t make a sizeable difference. The industry will undergo its own wash-out as marginal high cost capacity eventually exits the market - the doings of the invisible hand if you so will.

This is where ULCC has an advantage; they have a net cash balance sheet and so they’ll be able to take the pains of price wars much better than levered counterparts. As a portend to the turbulence the industry will likely encounter, ULCC revised Q3 23 guidance, taking pretax margins down from 4 - 7% to -4% to -7%.

Moving onto JBLU and SAVE. Both entities sport levered balance sheets and have had troubles making money of late. Just tonight, JBLU affirmed Q3 23 revenues and CASMX at the low and high end of guidance respectively. SAVE has also guided down earnings for Q3 23 from -6.5% midpoint operating margin to an ugly -15% midpoint margin - the report highlighting “promotional activity with steep discounting for travel..” so Barry’s sentiments aren’t far from reality. Again, the ultra low cost carriers have struggled to make a dime in for lack of better words, peak travel demand period, and if the three headwinds cited by Barry are true going forward, it’s tough to see how much equity value JBLU and SAVE will preserve as standalones (at least post-break and near-term); hence “their financial wherewithal is dependent upon this merger now.” FWIW, the legacy carriers have been minting good money through this period.

The next issue is the GTF engine recall which affects SAVE and JBLU disproportionately relative to competitors since they have relatively larger portions of their fleet being GTF-powered Neos - note that SAVE is the largest operator of said Neos in the US with the highest number of engines produced during the 2015-2021 period in question. Moreover, SAVE has cited Airbus delivery delays that would continue into 2024 and beyond. In other words, SAVE will be facing capacity issues in the medium-term and both JBLU and SAVE would cede market share as less affected counterparts fill the gap - which Barry implies, is good for ULCC.

Again however, Barry downplays the GTF issues and points to the merger “looking more and more likely based on news (divestitures) out today” as the key big opportunity for ULCC.

In sum, it appears that SAVE and JBLU standalone may be in for a pretty rough ride ahead as the industry tails off cyclical highs into a tornado of headwinds and maybe this lends some strength to why the two entities deserve to merge, if not, to protect the economic benefits (jobs, service) provided by both airlines. At least Barry seems to think so.

Do note that Barry has been in the industry for decades, beginning his career as Chief Marketing Officer for SAVE, before hopping onto Frontier so this guy has seen it all and knows what he’s talking about.

Divestitures

Horizontal mergers typically require structural remedies to assuage the plaintiff. They’ve historically worked quite well to satisfy the DOJ; there’s been tons of mergers within the space and Doug Parker aka King of Airline Consolidation, famously stated that “consolidation of the airline industry is inevitable.”

Some major mergers in the recent past that required structural remedies include the United-Continental merger, which was approved after slots from Continental’s key hub, Newark, was transferred to Southwest, and the American and U.S Airways merger, which was actually settled early (few weeks before the scheduled trial date), after the defendants agreed to divest slots at Reagan National Airport and La Guardia Airport to low cost carriers.

In this current case, JBLU has announced definite divestitures in June and September as structural remedies for this horizontal merger. Of key importance is that these divestments would be to ultra low cost carriers. In the DOJ complaint, a few cities/airports were mentioned multiple times, key e.g.s being the i) Boston-Miami/Fort Lauderdale routes, serving 1.5m passengers annually with JBLU and SAVE accounting for ~50% of the market and ii) Boston - San Juan, with both airlines accounting for ~90% of the market. The DOJ is concerned that the merged entity would essentially dominate these routes - in e.g. ii), proforma JBLU would essentially own ~90% of the origin-destination pair, far too concentrated for the DOJ’s liking.

Hence,

June divestiture

JBLU will transfer to fellow ultra low cost carrier, Frontier, all of Spirit’s holdings at LaGuardia - 6 gates at the Marine Air Terminal and 22 takeoff and landing slots.

Apparently, Frontier barely operates from LaGuardia while Spirit operates quite a few routes and so Frontier stands to benefit here. Note that the NEA ruling touts “opportunities to obtain slots at LaGuardia.. are exceedingly rare.”

September divestiture

JBLU will transfer to Allegiant (ALGT) all of Spirit’s holdings in Boston and Newark - 2 gates in Boston, 2 gates in Newark, 43 takeoff and landing authorizations in Newark - and five gates at Fort Lauderdale.

For Boston and Newark, ALGT runs low frequency routes primarily from smaller cities whilst Spirit operates frequent flights to major cities.

For Fort Lauderdale, ALGT runs active operations but SAVE is its only other major ultra low cost competitor, so the elimination of SAVE unwittingly creates a “monopoly” in the ultra low cost competitor segment for affected routes.

This throws up some debatable issues as all remedies must replace competitive intensity that would otherwise have been lost from the merger and so the burden of proof is on the defendants - whether the divestitures are sufficient or not. It is worth noting that gates and slots are in short supply at major airports and it would be nigh impossible for competitors to compete without access to said assets. Apart from the unintentional “monopoly” mentioned above, a key concern as mentioned in the complaint is that the divested assets will not be run the same way it was when Spirit operated them. For e.g. Spirit operates frequent flights from Boston and Newark and ALGT may not be able to replicate that.

As mentioned, divestees are all ultra low cost carriers with similar cost structures (as measured by CASMX). In fact, ULCC has operated at a lower cost structure than SAVE over the last 2 quarters. I provide JBLU (a non ultra low cost carrier) as a contrast.

In any case, what these divestments show is that the defendants are willing to play ball, to negotiate and make concessions if necessary to assuage any competitive concerns voiced by the DOJ. This is exemplified by JBLU not appealing the revoking of the Northeast Alliance (NEA) (essentially a merger in substance (not form) with AAL), since it served as a major overhang lift for the merger with SAVE.

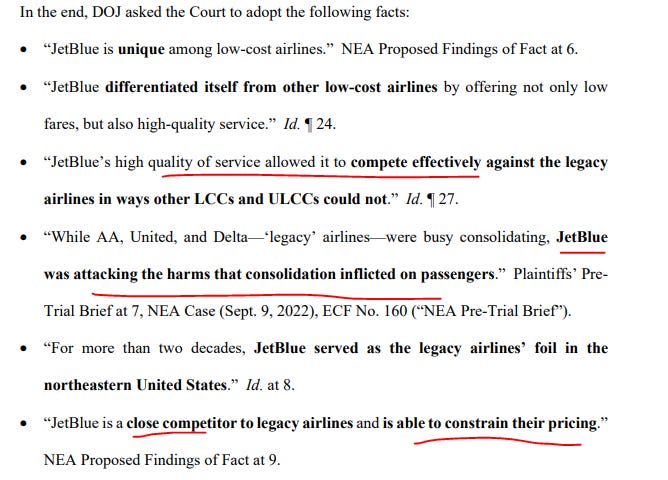

Judicial Estoppel

Another recent defense wrought by the defendants is evoking judicial estoppel - essentially “an estoppel that precludes a party from taking a position in a case that is contrary to a position it has taken in earlier legal proceedings.”

Basically, last year, the DOJ in its complaint against the NEA, described JBLU as a maverick - an independent player that doesn’t price-coordinate with the legacy carriers - and gifting the “JetBlue effect” to boot - whereby fares fall whenever JBLU enters a market.

Now, the DOJ has turned 180 degrees and argues that the proforma JBLU will be anti-competitive in that it’ll no longer retain “maverick” status and will likely align it self with the legacy carriers via tacit collusion shenanigans and what not.

This change in tone has been criticized a fair bit by many but just to lend credence to the DOJ, I don’t find it particularly unreasonable. Firms enter entrenched markets as disruptors but typically, as they scale, lose their initial identity (for various reasons) which eventually loosens the locks of their gates, providing opportunities for entrants to disrupt them. Clay Christensen has discussed this in depth in his writings. In other words, being a maverick is not necessarily a stationary property and it’s not unreasonable to argue that a larger and more monolithic JBLU will operate differently than when it was small and nimble.

On the other hand, this can be rebutted by the fact that

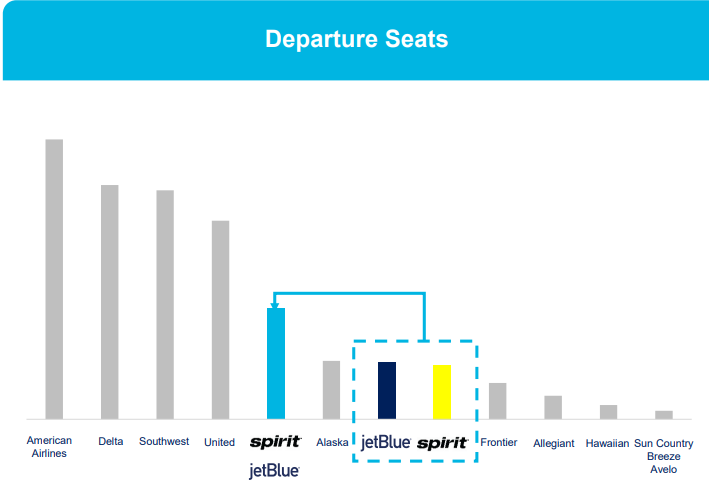

The legacy carriers already control ~80% of market share and the merger between JBLU and SAVE would be like the union of bugs; the proforma entity will be a fair bit larger (9% market share) but still much smaller relative to the likes of the big 4. Again, if monolithic giants are really the key issue here, why not break up the big 4 instead?

Judge Sorokin, in the NEA trial, ruled that JBLU would maintain maverick status regardless of whether it was a traditional low cost carrier (LCC) or a hybrid (between LCC and global network carrier (GNC) e.g. AAL, DAL) - the implication that a larger JBLU doesn’t ipso facto mean that JBLU jumps into bed with the big 4.

Spirit-Effect

The next issue discusses the “Spirit-effect” which both SAVE and JBLU didn’t exactly acknowledge in their response. Part of the argument is that the Spirit-effect lowers fares more than the JetBlue-effect and so customers will be hurt when SAVE no longer exists.

First, it’s worth noting that base-fare comparisons in a vacuum really doesn’t make sense. The ultra low cost model employed by SAVE unbundles ticket prices - depressing base fares to drive “top of the funnel” demand leading to higher load factors, which is then compensated by gouging on ancillary services. What truly matters is what the average customer pays bottom line. Moreover, many hybrid or legacy carriers offer competitive tiers that match the ultra low cost model - for e.g. JBLU offers Basic Blue.

I’ve googled around and for e.g. this simple study documented that a roundtrip flight from South Florida to NYC during the busy summer month of June costs $505 with Spirit and $546 with JetBlue’s Blue Basic, a ~7.5% delta, base fare. For this additional 7.5% with JBLU, you get a lot better service, leg-room, food - the utility of each dollar spent is up for debate and the bottom line may be more similar than not if the SAVE customer tops up on ancillaries because he/she missed breakfast.

Secondly, a study (pg41) conducted by Compass Lexecon showed that the JetBlue-Effect lowered average fares by 15.6%, not too far from Spirit’s 16.9%. The results are, albeit dated, statistically significant at the 1% level and the adjusted R-Squared of the study lends credence to the regression model.

While simplistic, the main point of the illustrations above is to demonstrate that the whole argument over the Spirit-effect may quite simply be strawman in nature; even if it’s effects exceed the JetBlue-effect, it’s hard to argue if it’s meaningful at all.

On Pricing

To further countenance this point, the DOJ asserted in the NEA trial that i) there’s a lot more nuance to price competition than just vanilla fares - consumers often want a good blend between price and service, ii) there is always room for new disruptors (as was JBLU) to mend the wounds of consolidation, iii) JBLU is a uniquely strong force against the 80% market share of legacy carriers.

The DOJ and government’s concern that the merger will lead to higher prices and therefore hurt the consumer, is a pretty lazy argument. I reckon it would be a lot more wallet-friendly if greenwashing/ESG agendas are retracted and the President stops messing with the nation’s SPR. As we have seen, Frontier is already honing down its cost structure, preparing for fare wars in as the industry tips into capacity surplus - so there are headwinds there.

It’s intuitive and, using the DOJ’s measurement methods, to assume that a higher Herfindahl-Hirshman Index (HHI) - a measure of market concentration - is positively correlated with higher industry prices. And yet, a wide body of research has shown that this simply isn’t true for the airline industry (1 , 2). On the contrary, in spite of the rampant consolidation over the last two decades, inflation-adjusted average fares and inflation-adjusted domestic prices per mile has declined over time (pg 47); competitive intensity has actually increased, as the average number of competitors per domestic city-pairs have increased (pg 15).

There’s a lot of studies out there that analyze post-mergers - this technical paper analyses the AAL merger from 2011-2016.

Interestingly, the authors documented fare decrease post merger in the markets analyzed (though it’s hard to delineate endogeneity - the passing of falling oil price cost savings from airlines to customers). Overall, the authors conclude that consumers benefited from the merger (more extensive network) and that the slot divestitures worked out well since it provided an entry point for low cost carriers, which serve as price watchdogs.

In sum, I find that the question (or any derivative thereof) of “will JetBlue raise prices?” as a fulcrum argument for anti-competitiveness rather insipid as it disregards a whole bunch of variables that truly make a difference in terms of consumer surplus - which is what really matters. Again, JBLU is desperate to get this deal done and if Basic Blue is demanded to be kept, it’s a concession JBLU would definitely make.

Whilst the DOJ also made a strawman argument in its complaint that the airline industry faces significant barriers to entry - again this is arguable as airline entrants have dwindled over the last few decades. But, again, the proof is in the pudding - the recent emergence of Breeze and Avelo (both ultra low cost airlines) from the gulf of COVID serves as a good counter to this point; so yes, whilst SAVE might disappear, this doesn’t mean the gap will be unfilled (reminder that Frontier sees this as a big opportunity to capitalize on). Moreover, low cost carriers tend to see their cost advantage erode over time as labor demands upward pressure on wages - Southwest has seen its cost structure slowly resembling that of legacy carriers over time. Hence, it is advantageous to have new entrants with cost structures at ground level.

Final Thoughts

Anyway, there’s been a few great writeups on this situation so far and I hope I’ve provided a different (and hopefully close-to-accurate) angle on this through this short ramble.

The DOJ’s allegations seems rather shallow in many respect and there is often a huge disparity between the hypothetical post-merger landscape conjured by the DOJ versus true reality (same for the suit against Spectrum Brands and Activision).

I think the right lens to think about this merger is from a consumer surplus perspective. JBLU provides top-class service but is regionally limited as most capacity is in the Northeast and Florida corridor. Spirit on the other hand provides orgasmic fares but service is atrocious. From the standpoint of fighting against the legacy carriers - the customer demography is very different and most flying legacy carriers won’t even think twice of Spirit. From the standpoint of a consumer surplus perspective, the merger allows JBLU to expand its national footprint, increasing consumers’ exposure to good service without a drastic price tradeoff - the JetBlue-effect remains alive and well.

Some have voiced concern about the Department of Transport (DoT) intent to block the merger which was quite a surprise though JBLU’s commentary on this is rather instructive in that simply winning the case against the DOJ should more or less solidify the victory.

There are risks involved here which I mainly attribute to the political side of things; one might argue that this merger be the “scapegoat” - the much needed win for Biden, after all the failed antitrust litigations (1 , 2); on the other hand, Biden’s pro-competition agendas seem to be better applied to the world of big tech, consisting of the strongest companies of all time. However, little wins matter - FTC blocked Meta’s acquisition of Within despite the judge determining the deal to be anticompetitive.

And yes, whilst high profile cases have wiggled through the cracks, learning the outcomes of recent coin tosses doesn’t necessarily pin the odds of a head higher on the next flip (a flawed analogy for various reasons but you get the point). A key example would be FHN - the regulators have not denied a bank merger in **twenty years but finally drilled the nail down with FHN, the skeleton being TD’s AML practices. But again back to Robin’s comment in the picture above → winning the trial is the main obstacle to closing the transaction.

Valuation

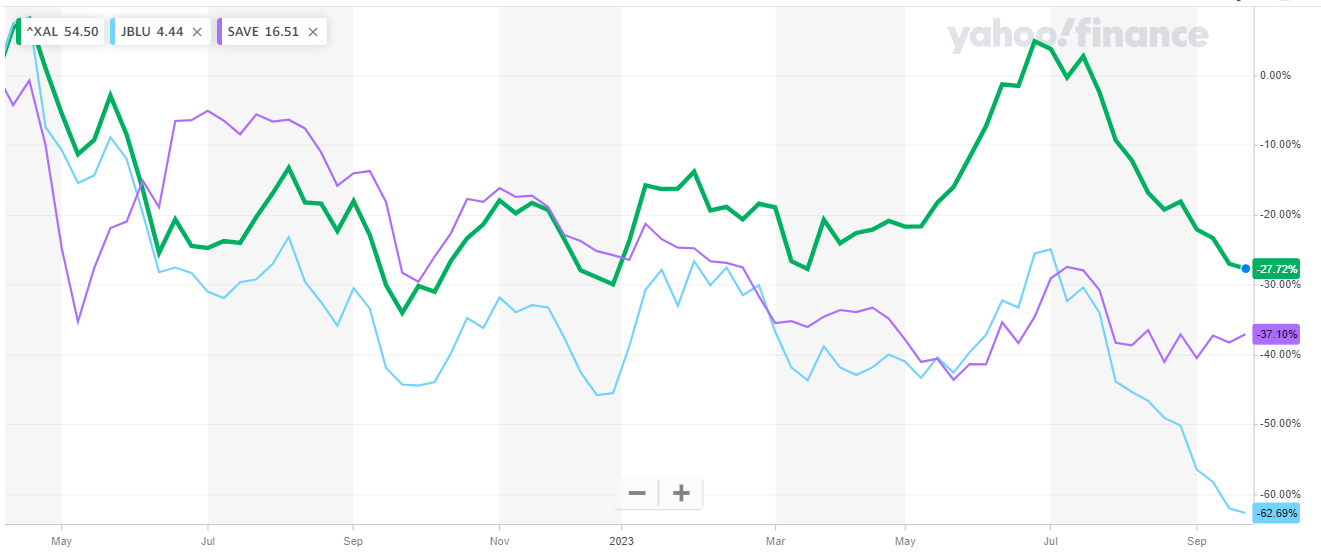

Depending on how you view the downside for SAVE, I’m thinking $8-$12, which may be too drastic still considering Spirit has ~$13.50 of book value and may bleed another $1-2 of EPS the next 6 months and so the low to mid point of the range would be a fair bit below n6m book value (~$11.50-12.50). Then again, SAVE’s been plagued with the GTF engine issues and other victims have seen their stocks crumble → VLRS in Mexico and WIZZ in UK (check out the relative performance to RYAAY who’s going to be taking some share).

Regardless, the market is pricing in a probability of around 20 - 35% chance of deal closure whilst the options market is pricing around ~25-30% chance of closure so perhaps a guesstimated downside of ~$10. Overall, I think the odds of closure is pretty much a coin flip and more so we could argue the bet is mispriced here.

Oddly, the market appears to be pricing a high closure probability in JBLU’s stock. JBLU trades at less than half of book equity which only dipped after the acquisition announcement implying that the market absolutely detests this deal and foresees imminent distress. The stock has declined more than 10% post the September divestment announcements and yet SAVE has not barged!

Just to illustrate that JBLU’s market-implied distress isn’t a present balance sheet problem, JBLU currently has ~1.7bn of cash against ~3.2bn of debt; they also have a unencumbered asset base (not so clear what is in this but probably consisting of aircrafts, engines etc.) of ~2.5bn and even haircutting this by 50%, still yields > 1bn of liquidity, not factoring in another access to $600m revolving credit facility. In other words, liquidity for status quo operations isn’t an issue and these lines will be tapped for the acquisition. Perhaps, as a hedge, one might go long JBLU as well, I’m not sure the stock dumps further even if the merger proceeds - it seems like whoever wanted out, is out already.

Disc: Long SAVE common, Jan 24 and March 24 bull spreads, Jan 25 JBLU calls

Thanks for a good write up. With the recent development any update where you see SAVE trading in a break scenario?